Arisen in the 1990s, the television format of the documentary series today lives mainly in streaming. There, there are several Chilean productions available that are being consumed in various parts of the world. There is an industry that is growing and developing in quality and quantity, but Chilean television not only does not participate in this story but even turns its back on it.

By Pachi Bustos for CCDoc

In the born-after-dictatorship television, documentary series made their debut in Chile. At that time, programs such as the ethnographic and naturalistic Al Sur del Mundo (1982 – 2001) or El Mirador (1991 – 2003) and Los Patiperros (1998 – 2002) were shown and portrayed life stories and social issues with appealing audiovisual proposal and documentary film resources. The series multiplied and diversified, but today they have almost completely vanished from television and, since a decade ago, have started a new life on streaming platforms. Although fictional series are the most widely consumed there, documentary series have also had several successful and celebrated titles, and this is on the rise, and Chilean series have gradually entered this circuit.

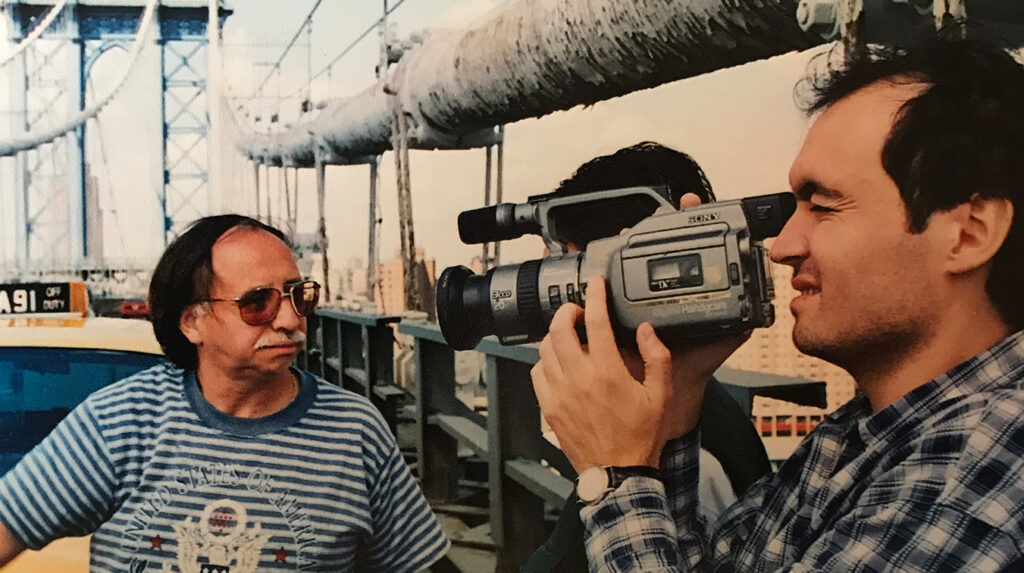

Los Patiperros (1998 – 2002)

A powerful example is A Sinister Sect: Colonia Dignidad, premiering on Netflix in October 2021. Created by documentary filmmaker Cristian Leighton and made in partnership with the German production company house Looks Medienproduktionen. Using an incredible unpublished archive, this story, which took place in the Ñuble region since 1961 and was not known in great detail by Chileans, was told in six episodes. Subtitled in thirty languages, it is now available in dozens of countries, with good audience figures in places as diverse as Japan and Turkey.

A Sinister Sect: Colonia Dignidad

Leighton is also a well-known documentary filmmaker of films such as Nema Problema (2001) and Ultraman (2004). From that experience, he first treasures the possibility of reaching bigger audiences that the television documentary series offers, especially considering how the box office behaves with Chilean documentaries. There are milestones such as Red Eye (2010), which brought almost one million viewers to theaters, and others corresponding to renowned documentaries such as Patricio Guzmán’s Allende, which brought in forty thousand, or Maite Alberdi’s Tea Time, which brought in over twenty-eight thousand. However, it is common for a documentary to bring less than five thousand viewers to the theaters.

Tea Time

In this regard, Leighton says: «the documentary film has had a hard time and still has a hard time reaching a good part of the population. While a series like La Sangre Tira, from 2013, for example, had an average rating of five points, equivalent to 400 thousand people… How I wish that documentaries were seen by that number of people».

Television documentary series had what could be called their golden age until the early 2000s. And from then on, another story began. In those distant years, programs such as El Mirador, Los Patiperros, El Triciclo, Testigo, or Cine Video were broadcasted in prime time and had respectable audience figures. However, that is part of history, and today national channels simply do not produce nor exhibit documentary series.

Yet, there are some exceptions where productions financed by the National Television Council -the only national instance that supports this genre’s production- stand out, such as the successful What is your Dream? A series directed by Paula Gómez, its first two seasons won Emmys (in 2011 and 2015) and was broadcasted by TVN, or Tráfico Ilícito, produced by Diego Breit of Glaciar Films, and which received support from CNTV in 2016.

Tráfico Ilícito

«Before, you could come to television with a good idea, and they could finance it, but then budgets went down, and there’s not much direct commissioning anymore,» says Juan Pablo Sallato of Villano production company.

It is undeniable that television no longer has the resources from before since the rating numbers have reduced, and with that, advertising has decreased. Some television stations’ crises have been recurring and flashy, including the dismissal of workers, strikes for non-payment of salaries, radical outsourcing of services, and reduction of the program schedule. Among many other contents and formats, documentary series practically disappeared.

Not entirely, of course, but formats and content seem to have become standardized. Gonzalo Argandoña, from the production company Cábala, describes the documentary offer of today’s TV as a domain of travel or gastronomy programs; «with all due respect to their contribution and their producers, these are programs made with a guerrilla scheme, sometimes with one or two people as the whole team, and in the face of that, a different proposal, perhaps with a more complex production, is left out.»

Carola Fuentes, from Ventana Cine, sums it up a little more severely: «the aim is for productions to have an immediate result in tune, which sacrificed the diversity of content and homogenized the offer for the audience.»

But not only series producers and directors share this diagnosis. The President of the National Television Council (CNTV), Faride Zerán, gave a similar review in an interview with El Mercurio last July. «Television is becoming less and less diverse. It has been taking fewer and fewer risks and has made fewer and fewer bets to incorporate new themes and innovate in formats and topics.»

Today, without television screens, the Chilean documentary series genre essentially navigates the streaming platforms. Although another story and another industry are already happening there, for the series makers, television is still a space they don’t want to leave behind.

Sylvain Grain from the production company house Raki Films behind the series Children of the Water, which has been co-produced with the channel Señal Colombia, expresses it more from the audience’s view than from the industry’s: «we make the series so that people learn and have awareness about the water issue, and to reach the highest number of spectators. With this theme, we should reach open television. It’s not a financial issue but the impact of what we do.»

New spaces

Digital platforms of audiovisual content began to appear more than a decade ago, but the two years of the pandemic heavily multiplied its presence in the world. A concrete example: On March 21, 2021 -one year after the beginning of the quarantines- Netflix premiered the documentary series Tiger King in the United States, with the story of eccentric tiger collectors and private zoo owners. In its first ten days alone, it was watched by more than thirty-four million viewers in the United States, that is, by one out of every ten Americans.

This phenomenon has its correlation around the world, although, in Chile, there are no such precise numbers because, to tell the truth, the absence of public figures is a commonplace occurrence in streaming platforms worldwide. In any case, the impact can be seen in other signals, such as the general relevance of A Sinister Sect: Colonia Dignidad. Furthermore, the documentary series generated public discussion and was a topic in social networks, and even a State Minister involved in the story, as the series showed, had to explain his participation in the events.

For Cristian Leighton, the series’ success lies not only in the story but also in the new format and the facilities it offers the audience. «For many reasons, the number of people who watch it on Netflix is much higher than if it was shown on open television: you can watch the series whenever you want and is not subject to the channel interrupting it with commercials or putting schedules, cuts, merchandising on the screen… The open TV model is in crisis», says the director.

Like Netflix, many platforms have also opened their screen to Chilean documentary series. For example, the series Libre, by the production company house Villano, became the first Latin-American non-fiction production to be acquired by Amazon. Financed by CNTV Funds and with the support of ProChile, Libre portrayed the world of inmates, exploring how they reintegrate into life once they are released. For its director, Juan Pablo Sallato, this series is based on local themes but transcends them: «it is a prison police genre, and if you skillfully construct its audiovisual narrative, it is interesting to watch anywhere because, in the end, they are good life stories.»

For Miguel Soffia, director and executive producer of We are South, it is essential to connect with the audience and offer them content with greater depth for their lives. «For me, it is crucial to create projects that generate dialogue, nurture conversation, and can install themes and contribute to society: it has to do with a public vocation.»

Markets

The arrival of Chilean productions to other countries’ streaming circuits also means a new space in relationships: the world’s industry meetings are held in the so-called «international markets,» where production company houses’ representatives, television channel programmers, distributors, and sales agents meet.

These markets represent an essential showcase to generate partnerships, seek funding, and develop projects. Among the main ones are those associated with the festivals of IDFA, Hot Docs, Sheffield Doc/Fest, Cannes, FIC Guadalajara, Dok Leipzig, or the markets of Sunny Side of the Doc and DocMontevideo, among others. Through them and others, in different stages of production, many Chilean documentary series projects have passed through, several of which have been very successful.

Three examples are The Culture of Sex (2014), by Villano Producciones, which was a pioneer in international markets and was shown in Italy; Children of the Stars (2014), by Cábala Producciones, which was the first Chilean scientific series shown on Netflix, Natgeo, and channels in Colombia, Spain, Uruguay, Mexico, Sweden, France, Belgium, and Switzerland and is currently developing its third season; and Nuevo Mundo (2020), made by the Buenos Aires-based Tercer Mundo, which was shown on television in Argentina and Brazil, and in Chile, which aired on La Red in March 2020. And recently, in 2022, a series that received multiple Emmy nominations, produced by Netflix, Our Great National Parks, which chapter Chilean Patagonia, was directed by Christian Muñoz-Salas and Ignacio Walker, who spent four months filming in that area of southern Chile. Muñoz-Salas’ work was nominated for «Best Cinematography for a non-fiction program.»

Our Great National Parks: Chilean Patagonia

Paulina Ferreti, from Tercer Mundo, appreciates how these meetings also help to improve the projects. «For us, the markets marked a before and after. They don’t necessarily work the next day, not even for the project you talked about, but you build a network, and the possibility of being in a laboratory, of sitting down and telling the idea to one person and then to another, develops trust. This way, the projects grow and take on an external life; even when they are proposals in development, they can become real».

All those screens outside Chile, where Chilean series have been screened, have been accessible through these markets, which have been reached with greater strength thanks to the creation, four years ago, of a sectorial brand for the documentary industry. Today Chiledoc -a public-private alliance between ProChile and the Chilean Documentary Corporation CCDoc- is a concrete support for promoting and positioning this productive sector of the creative industries internationally.

Many documentary series have since accessed different co-production and distribution agreements with that backing in their productions, in missions financed by the Ministry of Cultures, Arts, and Heritage, or by ProChile.

«It is in the markets and in the industry sections of festivals where things happen, and co-productions and socialization are generated,» says producer Miguel Soffia of We are South. This Chilean production company has collaborated, among others, with documentary series for the BBC, Discovery, Al Jazeera, and Netflix, with whom it produced the series 72 Dangerous Animals: Latin America.

Financing and the future

To finance a documentary series in Chile, everyone has to bet on the same sources, which are essentially two: the Audiovisual Fund and the National Television Council, CNTV.

The first is resources that CORFO previously administered but have now become the Fund for Strengthening Audiovisual Projects as part of the Ministry of Cultures, Arts, and Heritage Fund. The resources granted are for the initial stage of the projects (presentation texts, research, scripts, budgets, and trailers).

The second is for the complete television series production, granted annually since 1993 by the National Television Council. According to the law, its mission is to «encourage the production of quality and cultural programs.» Yet, although essential, the CNTV’s support is limited to the enormous number of proposals. Paulina Ferreti of the production company Tercer Mundo puts this disparity in context: «in a CNTV project, you are left with the opinion of a jury, which is sometimes very hermetic. But when you participate in markets abroad and meet people, you understand that we are shutting ourselves in without any sense. Thirty countries outside are interested in this, and it’s good that we are looking over there».

«I value CNTV’s contribution. The situation would be truly dramatic without this fund,» says Carolina Fuente. Her partner, Rafael Valdeavellano, also values diffusion. «The obligation to broadcast them on an open signal means that many of these contents can be seen.» However, they all agree on the need to look for sources of financing in the streaming circuits and the doors opened by the markets.

And this is how the genre, born thirty years ago, is drawn in today’s Chilean audiovisual production. In its processes, it articulates many factors: the development of the industry; the tastes of the audiences; the type of consumer of the platforms; the history of the documentary genre; and the experience of its filmmakers.

The results transcend audiovisual production. «At the level of artistic and creative expression and the construction of identity and country image, the contribution made by the world of series is very relevant,» says Gonzalo Argandoña.

In the interview mentioned above with El Mercurio, CNTV president Faride Zerán revealed an important fact about how Chileans watch their television. «In 2017, according to our surveys, 42% of audiences were satisfied with television; in 2021, only 24%. So that tells you something is happening.»

«Chilean audiences are intelligent. They value interesting content, unlike what they are used to seeing, a showbiz character visiting places as a tourist,» says Carola Fuentes. Moreover, documentary series are talking about Chile, and possibly there are many Chileans interested in watching them.